How to transform your smartphone into a real-world Star Trek tricorder

Image: Brad Chacos

Image: Brad ChacosWhen the first flip-top phones appeared in the ‘90s, prompting amazed gasps of, “Hey, this is just like the communicator in Star Trek!” it felt like we were on the cusp of an amazing sci-fi future. These days, however, James T. Kirk’s handy interstellar mobile device looks a bit clunky—and it’s shamefully low on functionality. With no text or web capability, the communicator’s only uses are voice calls and the occasional deployment as a medium-yield timed explosive.

To compete with today’s phones we’ll have to turn to another bit of Star Trek equipment: the tricorder. Fans will know the tricorder as the palm-sized (at least by The Next Generation) device filled with enough sensors and computers to scan the surrounding area, allowing its wielder to deliver whatever exposition the Star Trek writers needed the audience to know.

Sure, the tricorder might seem like a convenient plot device, but your own humble phone has a surprising quantity of sensors and computing power at its disposal. With a few choice app installations you can leverage that power fully. Soon you will be the one scanning for new life forms and subspace disturbances.

It’s life, Jim…

One tool on your phone that’s only going to become more powerful is photo recognition. The more photos we take and upload, the more data computers have to learn from, the more accurate their guess work gets.

Leaf Snap

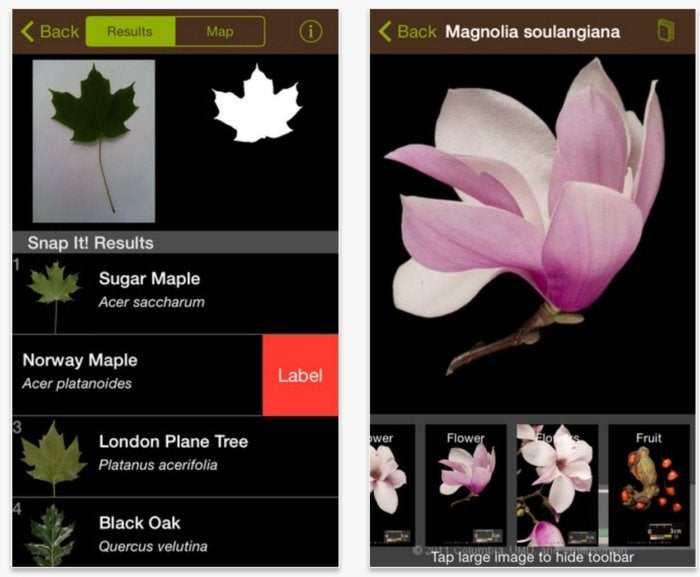

Leaf SnapLeafsnap

Apps such as Tree ID, from the Woodland Trust in the UK, and Leafsnap on the iPhone use visual recognition techniques on a photo you take of a tree’s leaves to identify its species.

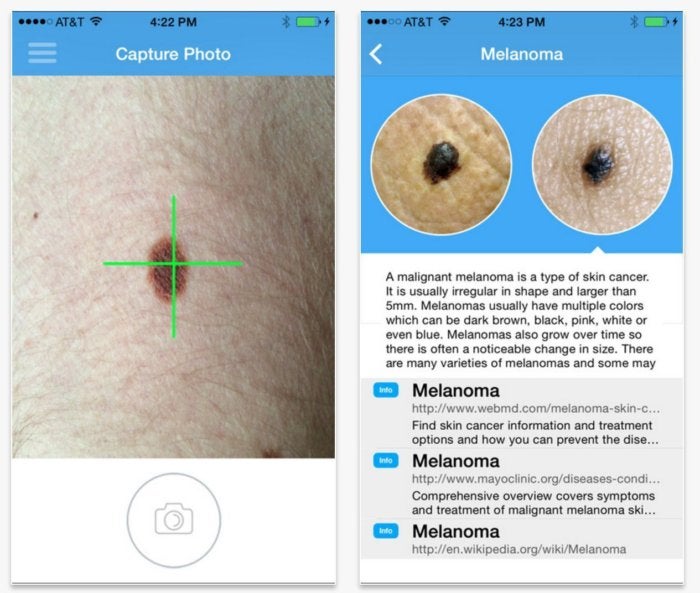

For a more practical (if potentially alarming) photo-recognition trick, you can use your phone as a medical tricorder and install the Lubax app to photograph any worrying moles, spots, or lesions and receive a diagnosis—although we wouldn’t advise substituting that for visiting an actual, real-life, non-holographic doctor.

Lubax

LubaxLubax

If you’re merely looking to detect life forms rather than identify them—handy for finding pesky xenomorphs on your ship—you can track them with a motion detector app. Or take a closer look at things using one of the various magnifier apps on the market. Or say you want to establish the size or distance of an approaching alien, you can do so with Smart Measure. It uses a combination of your phone camera and some high school trigonometry to measure sizes and distances at the tap of a touchscreen.

I’ve detected an anomaly

Those are all clever ways of using your phone’s camera, but there’s a lot more to your phone than that. You’re carrying a positive laboratory of scientific instrumentation in your pocket. For instance, starting with the obvious, your phone can pick up and measure sounds. Apps like Sound Meter allow you to monitor volume up to 100 decibels.

Magnetic Field Detector

Magnetic Field DetectorMagnetic Field Detector

More recent phones even have internal temperature sensors. Smart Thermometer allows you to access that sensor and track temperatures. But some of your phone’s sensors can be a little bit more esoteric. The Magnetic Field Detector app, for instance, lets you measure the location and strength of magnetic fields. You know what has magnetic fields? Metals like steel and iron. Oh snap, now your phone’s a working metal detector!

Hailing frequencies open

More than that, your phone can track satellites. Satellites in space.

GPS status and toolbox

GPS status and toolboxWe don’t need to tell you that with Google Maps you already have access to a complete photorealistic map of the planet Earth and your position on it (which, by the way, is maybe a function the Enterprise should have used a little more often on their own tricorders). But that tracking works two ways. With GPS Status & Toolbox you can find the position of satellites, the strength of signal you’re getting off of them, the speed they’re travelling at, and more.

Boldly going where others have gone before

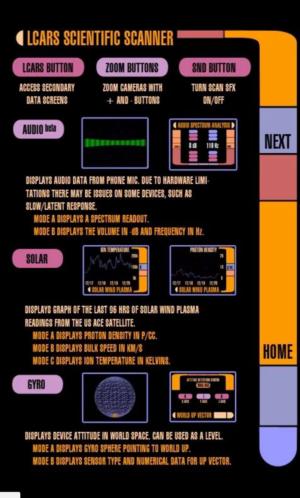

Scientific sci fi scanner

Scientific sci fi scannerOf course, if all that sounds like too much work (not to mention storage space) you can cut a lot of corners and simply download the Scientific Sci-Fi Scanner app.

The “sci-fi scanner” has access to a great deal of scientific data, including solar wind plasma readings from the US ACE satellite, the last 10 months of land surface temperature, sea surface temperature, vegetation index, chlorophyll concentration data, meteorological data, and magnetometer readings. All this data is displayed through an easy-to-read interface that, by some kind of huge coincidence, happens to look almost exactly like the computer interfaces in a TV show we can’t remember the name of.