How to use Raspberry Pi as a DNS server with dnsmasq

Image: Raspberry Pi

Image: Raspberry PiI love my little Raspberry Pi. The $35 computer has a ton of uses, from the utilitarian to the hobby project. But in practice, how many of us are going to build a homebrewed Amazon Echo? My guess is not many. But there is one use for a Pi that I’ve been a big fan of for almost a year: a simple DNS server.

DNS and dnsmasq

By making DNS requests from a local Raspberry Pi instead of a remote server, you can realize a few advantages. Fetching any kind of data from a local area network will always be faster than fetching something from the Internet.

If you’re not familiar with how DNS works, I recommend reading Marco Chiappetta’s article about how to speed up your DNS. If it still sounds complex, there’s a comic series that explains how DNS works using cute cartoon servers.

The Linux program dnsmasq is a lightweight DNS and DHCP server that can be found in router operating systems like DD-WRT. While the Raspberry Pi may be a little underpowered for other routing and firewall functions, I’ve noticed that my Raspberry Pi 2 offers more than enough power to run dnsmasq. On top of that, the dnsmasq configuration files are much easier to understand than some other DNS servers.

Setting up dnsmasq requires setting up a server on a Raspberry Pi, which is its own task. The Arch Linux Wiki has a pretty good article on how to set up dnsmasq, and the main configuration file (/etc/dnsmasq.conf) is well documented. If you’re new to setting up servers, I recommend running Ubuntu on your Pi.

1. You can cache DNS lookups for decreased load times

One of the main advantages to running a local DNS server is that the server can cache DNS lookups for future use. While this seems trivial—you’re really only trying to get IP addresses for domains, after all—it can add up.

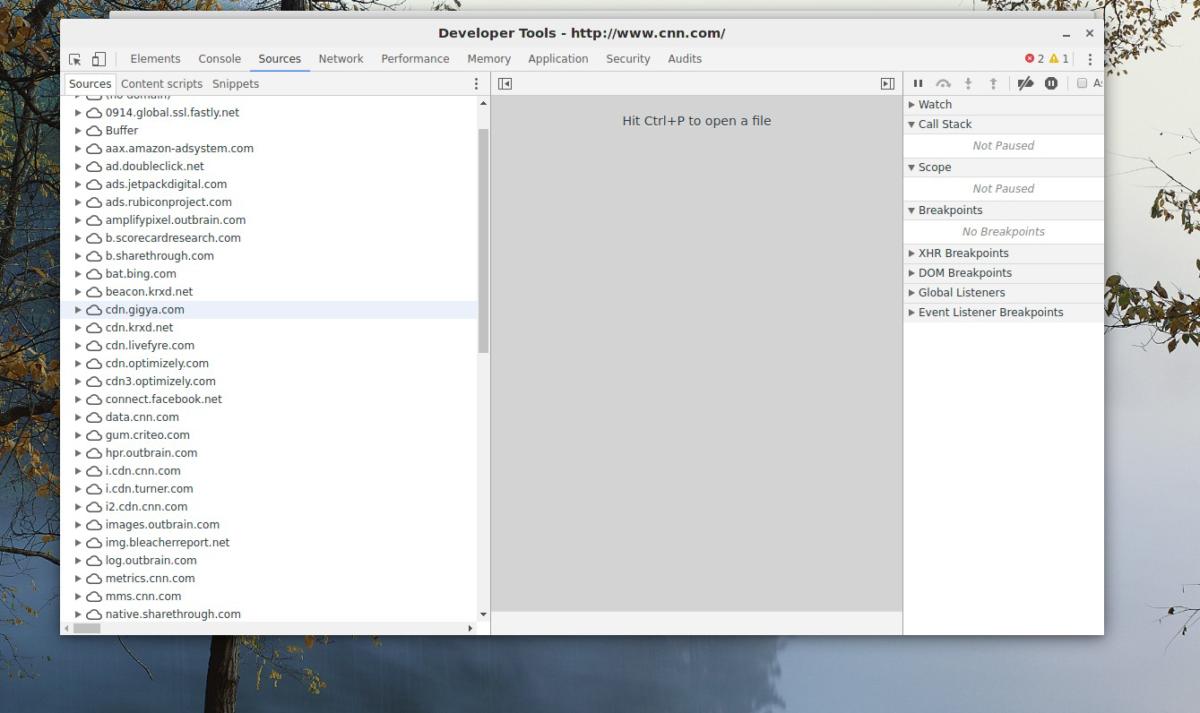

Alex Campbell

Alex CampbellThe list on the left of the window shows all of the domain requests made when opening CNN.com’s homepage. Note that some browser plugins (like Buffer) make their own requests.

When you load a web page, your device may perform a dozen or more DNS lookups. Obviously, there’s the website itself. But today’s websites may be loaded with Javascript plugins for everything from animations to analytics gathering. Each service requires its own DNS lookup. If the website uses a content delivery network (CDN) to serve images or videos, that’s another lookup. Then there are the advertising elements and social media buttons. And so on.

By caching these IP addresses, the Raspberry Pi cuts down on network latency because it’s on your local network. Granted, we’re talking about fractions of a second here, but those fractions of a second are what people pay for when they buy high-bandwidth internet plans from their ISPs.

2. You can redirect domains to machines on your LAN

One of the cool things dnsmasq can do is establish one or more domains for your local network and automatically assign devices as subdomains. For example, if I had a laptop named “alexlaptop” and had a network domain of “campbell.home”, I could ping my laptop on the network by typing ping alexlaptop.campbell.home.

Dnsmasq also allows you to predefine other addresses, which is useful for services you may have running on one or more computers. I could define “media.campbell.home” to point to the IP address of a machine running an Emby or Plex media server, or use “ftp.campbell.home” to point to a local FTP server.

If you want to run more than one service on a machine, you can direct several domains to the same machine and use a NGINX as a reverse proxy to redirect the traffic to a desired port.

3. Go nuclear on ads

There are many ways to block ads, but one of the lower-level ways to do it is via a hosts file on your local machine. A hosts file is the first thing your PC will use when looking up an IP, before it makes a request to a DNS server. This is effective at blocking ads because you can block an entire domain (like doubleclick.net) by defining it as 127.0.0.1 (also known as the localhost). By trying to look up the ad content at itself, it fails to load and effectively ends up being a blank section on a web page.

This is great, except that some malware and potentially unwanted programs can rewrite your hosts file. Luckily, dnsmasq can take the burden off your PC.

Dnsmasq has a number of ways it can provide hosts file-like behavior. First, it can use the hosts file of the Raspberry Pi itself. Alternatively, you can tell dnsmaq to use a dnsmasq configuration file. The end result is a hosts file-like blacklist that works for your entire local area network.

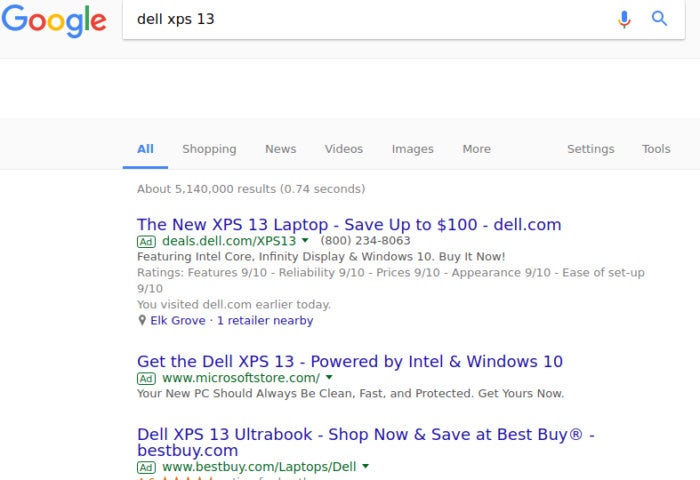

Alex Campbell

Alex CampbellIf you have ad domains blacklisted using dnsmasq, the links for the top three results in this Google search will be effectively broken.

Whichever way you go, you can find premade hosts or dnsmasq configuration files that contain the domains of the most common ad networks out there.

But going nuclear has a caveat, in that it sometimes breaks things you might not want breaking. An example I constantly run into is Google searches.

Sometimes the ads provided at the top of Google searches are exactly what I want (e.g. the home page for a company I’m looking for). If I click the ad that appears before the “normal” search results, the link is effectively broken.

In addition to breaking Google searches, using a blacklist approach will break some functionality for certain web sites. I should also note that a lot of news websites rely on ad traffic to keep running, so blocking every ad network en masse can hurt sites you actually want to support. On top of this, people who visit you and use your Wi-Fi may wonder why websites suddenly don’t work they way they’d expect.

If you want to temporarily un-blacklist sites while behind your dnsmasq DNS server, you’ll have to manually edit the DNS settings on your PC. You can also use a VPN to get around your local DNS, if your VPN provides its own DNS settings.

Conclusion

Like anything else, running your own local service means that you become your own tech support as well. If your Pi suddenly loses power or is unplugged from your network, the web will effectively stop working for your local network. (Direct IPs will still work.) For this reason, I usually make sure I have a backup DNS server IP (like Google’s at 8.8.8.8) in my DHCP configuration. That way, DHCP clients (like my desktop) will still have the backup DNS server to fall back on so long as the desktop isn’t shut off (or its DHCP lease expires).

The other thing you have to worry about is security. While your Pi can be safely tucked behind your home LAN’s firewall and NAT, you still need to keep the Pi updated with the latest security patches. While it’s a small task that’s easy to perform, it does require an extra periodic maintenance task.

With that said, if you’re comfortable hacking away in a command line and want a little more control over your local network, consider using a Raspberry Pi for a DNS server. After all, if it fails, you can always hand DHCP and DNS control back to your router.